By Nic Lindh on Monday, 17 April 2017

Wings of Freedom is a program run by the Collings Foundation that flies World War II-era aircraft around America so people can see them in person and optionally purchase flights on the B-17 Flying Fortress.

I figured they just can’t keep these old aircraft flying forever, so it was worth it to take a look and actually see them in person while they were visiting Phoenix.

There are four aircraft on display, a P-51 Mustang, a B-25 Mitchell, the last operational B-24 Liberator, and a B-17 Flying Fortress.

The last operational B-24 Liberator in the world.

All four aircraft are of course worth seeing, but the B-17 Flying Fortress is the icon of World War II bombers, the plane that springs to mind when you think of the bombing campaigns of the European Theater.

According to Wikipedia, each Flying Fortress cost about $240,000 in 1945 dollars, which is equivalent to roughly 3 million in 2017 dollars. 12,731 Flying Fortresses were built. War is expensive.

View out past the bombardier’s position.

What really struck me about the B-17 is how incredibly cramped it is—the crew members must have been tiny men, especially considering they were stuck in there for hours and hours wearing heavy clothing to ward off the bitter high-altitude cold.

Pictures don’t do the claustrophobic nature of the inside of the Flying Fortress justice—you really need to see it in person to appreciate it.

The ball turret on the B-17 is incredibly small.

How the air force got anybody to agree to operate the ball turret is beyond me—it’s incredibly small and the gunner is quite literally hanging outside the aircraft while enemies are doing their best to blast it out of the sky. Granted, the aluminum skin on the aircraft provides scant protection, but psychologically, being curled up in a little ball outside the aircraft at 30,000 feet must have been stressful to say the least.

The path between front and rear of the aircraft.

When it comes to moving around the aircraft, it involves walking a ledge across the bomb bay and having to squeeze across the support structures in the image above. Which as a burly 6-foot-2 man I could barely do wearing just a t-shirt and shorts, so for somebody to do it in full arctic gear seems incredible. Tiny, tiny people.

The cabin was of course not pressurized.

The best book I’ve read on the bombing campaign in the Western Theater during World War II is the masterful Bomber Command by the grand master of World War II history Max Hastings. The book focuses on the efforts of the RAF, but apart from the RAF flying at night, the RAF and the U.S. Eight Air Force faced many of the same challenges and issues during the campaign.

Including the morality of area bombings as a part of total war versus targeted strikes as well as the effectiveness of bombing raids altogether. World War II was the first conflict where massive bombing raids into civilian territory were technologically possible, so there was no past experience to draw on—everybody was figuring it out as they went along.

And of course, if you’re interested in World War II as a whole, the same Max Hastings wrote the ultimate book on the whole conflict: Inferno: The World at War, 1939-1945, which is so, so good and exhaustive—can’t recommend it enough.

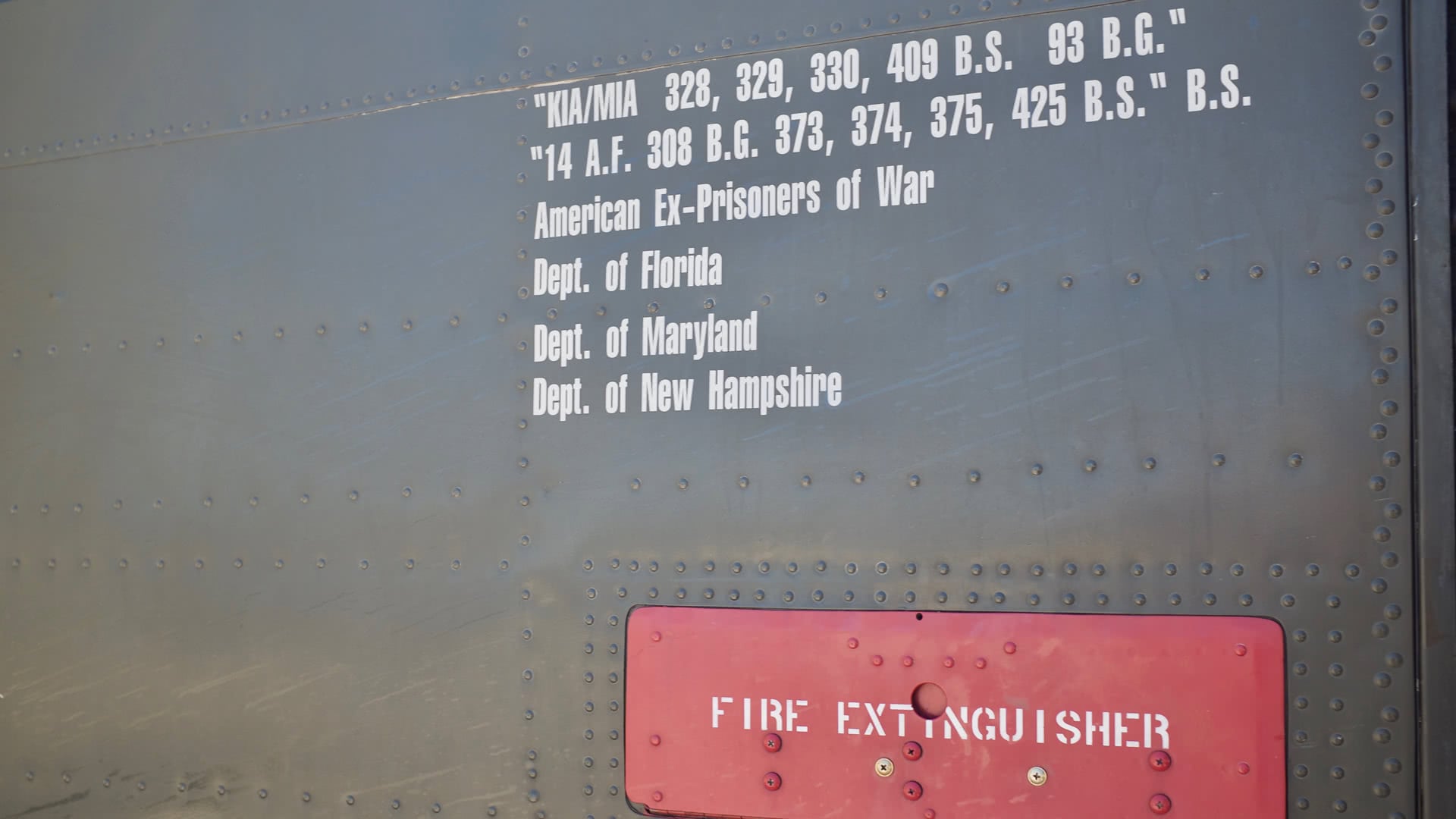

The human cost was enormous.